Trow Emilia: Hockney and Kellner – Interpretations of Cubism

‘Cubism remains perhaps the single most important development in the history of 20th century art’ -- Cox, 2000

Within this essay, I aim to define Cubist art and show how the Cubist movement has influenced modern day photographers. I will explore pertinent works of both Hockney and Kellner and discuss the similarities and differences in their interpretations of this most influential art movement.

Cubism was born in 1907 when the two artists Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and Georges Braque (1882-1963) met in Paris. They shared a vision that would break the rules of painting and create a new style of art. Life in the new century was very different; technology was evolving at speed and for the first time ever photography threatened to take over from art.

‘You can take in your hand; it is more like a perfume – in front of you, behind you, to the sides. The scent is everywhere but you don’t quite know where it comes from’ (Picasso)

Cubism is divided into two forms, analytical and synthetic. Analytical is pre 1912, it is called this because of its structured dissection of the subject as seen from multiple viewpoints. These fragments would then be assembled on the canvas to create a more complete and intellectually satisfying picture than that offered by conventional perspective. Synthetic cubism was developed after 1912 and is seen as the birth of collage. It is developed through a construction process rather than an analytical process. It is also more decorative, appealing and easier to interpret. It consists of using different materials to produce an image e.g. newspaper, cloth, sheets of music.

David Hockney (1937) is world renowned as an English painter, printmaker, stage designer and photographer. He is one of the most important figures in modern art. It is his role as a photographer that I wish to explore, particularly how the cubist movement influenced him and how he further developed it as an art form through the medium of photography. Hockney first saw the work of Picasso in the 1950’s, a time when Picasso was criticised by many in the art world. Hockney felt that Picasso ‘drew beautifully’ and taught him a lot about abstraction.

Hockney was a prolific photographer; his first camera was a 35mm Pentax. As his compositions became more complex he continued to use 35mm or a compact 110 camera. Following the roots of cubism, you can see that within Hockney’s images, surfaces dissect at different angles. Hockney aimed to produce pictures that had three artistic elements; which a single photograph cannot have, namely layered time, space and narrative. The first two of these are central cubist themes. Using the ideals of cubism to influence his photography he created photographs that encompassed these artistic elements, which had not been explored before. He stated that, ‘Cubism was a total vision’. Hockney developed a technique using Polaroid ‘joiners’. He first experimented with this in Los Angeles at the end of February 1982. These were made of a 7 x 16 grid of photographs. The narrative aspects are present from Hockney’s earliest works for example in figure 2 ‘My house, Montcalm Avenue’ (Figure 3). This series of photographs takes you on a journey through his house. The joiners can be likened to detailed descriptions of stationary subjects viewed from a variety of angles. Another example is ‘Sun on the pool, Los Angeles’ (Fig 3) the photographs are taken from above, it is made up of seventy-seven single Polaroid images. This work links very closely to a shoot I did at the Castle Cornet lighthouse where I took my digital camera and photographed the scene in different sections, the image does repeat itself in each frame but gives a really abstract look that I love.

Hockney further developed his interpretation of cubism to make photo-collages. These are eccentrically shaped pictures for example My mother, Bolton Abbey, Yorkshire (see fig 4). The ragged outlines correspond to the eye’s field of vision. By contrast to the more formal structure of joiners these photo collages direct ones attention much more dramatically across and throughout space. They provide opportunities for telling a story. This is probably a closer description of how we see the world, multiple viewpoints that are then pieced together to form a whole picture in our mind. He stated that;

‘Cubism made possible the idea of collage of the superimposition of one time level on another’.

These images depict layered time which is similar to narrative but subtler. A good example of layered time is in figure 5.This image shows a family chatting. As the people move they are photographed at different intervals but it is presented at once, Hockney has then joined the picture together so that the people have formed two heads and extra legs that gives a distorted look.

Hockney also uses reverse perspective for example, Jardin de Luxembourg, Paris (figure 6) which consists of a chair in reverse perspective; objects that are closer are smaller and the further away the object, the bigger it is made. The use of reverse perspective (which is surprising to a Westerner) is in fact very old, many pre- Renaissance and Japanese paintings have reverse perspective, as it allows you to see more of the scene, almost giving you a panoramic view of a subject.

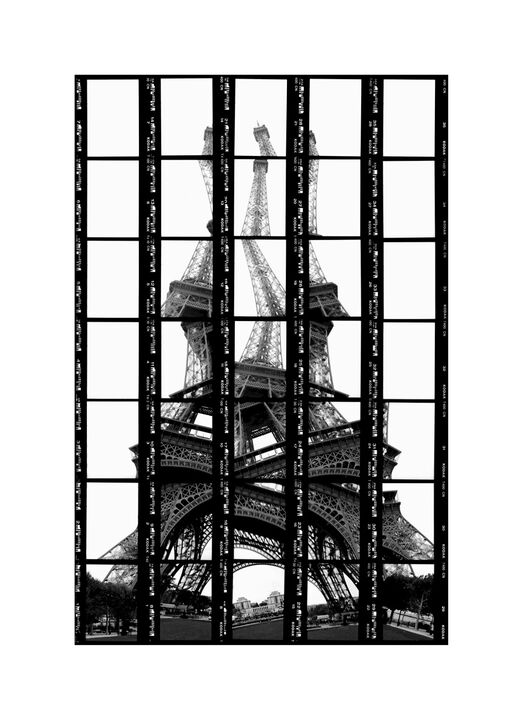

Thomas Kellner (1966) is a German photographer who ranks amongst the world’s eminent photographers of architecture. His work can also be seen to be influenced by the cubist movement. Kellner’s basic interest was in experimental and conceptual photography. After an adventurous project photographing the German border using a self made pinhole camera, he visited Paris. He decided rather than transporting an unwieldy pinhole camera, that he would use his normal film camera. He decided to try creating a contact sheep of fragmented images, of the Eiffel tower in a cubist style (figure 7).

‘During his college days Kellner had been profoundly influenced by the cubism of artists such as Braque and Picasso and also by the work of painter Robert Delauney’ (Skinner 2005)

The way in which Kellner produces his images is unique and differs from Hockneys work; he creates his pieces directly onto film. He prints every consecutive image from a roll of film, the final image being a contact print. The more film the larger the final image. For example for one film the final print is 20cm x 24cm, for 36 films the print is 100cm x 120cm. The frames are shot in sequence and then the strips are cut and mounted together. In my own work I have used this technique, as I was shooting a lighthouse it was pointless making the picture really wide so I stuck to 4 images along the top and 6 down the sides make a series of 24 images.

Each image has its own requirements, special arrangements and shapes. Kellner is meticulous in how he plans a shoot, consistent lighting it is essential. He uses a light metre to determine the best single exposure and uses it for each frame. It can take him from 30 minutes up to 4 hours. He sketches a story board to help him keep on track. I also used a similar plan when photographing so that I knew how many frames there would be, this meant I had to divide the images into equal amounts so that the whole lighthouse would fit in at the right focal length. Kellner used a Pentax MZS, zoom lenses and two teleconverters to do this.

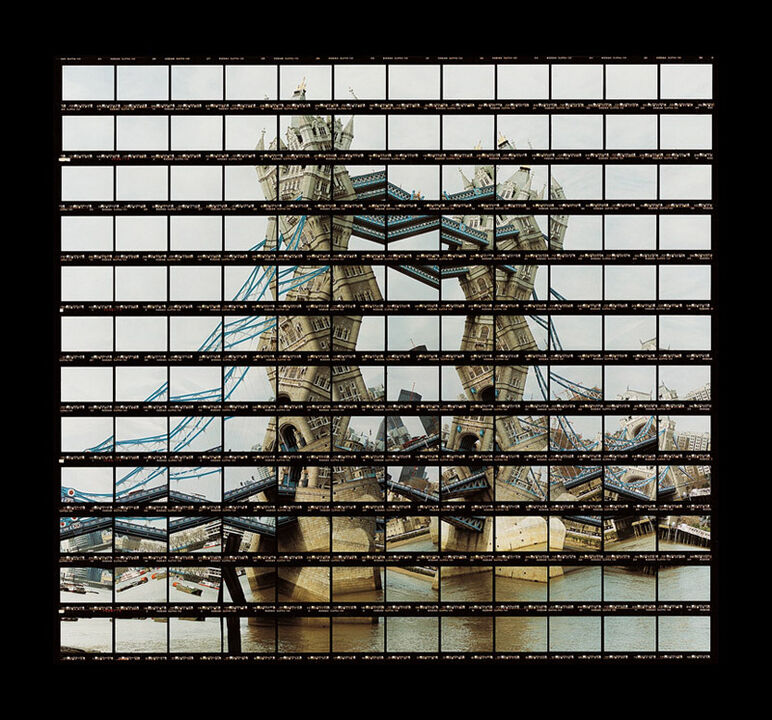

Thomas Kellner has been quoted as ‘deconstructing architecture as a visual language’ Whereas Hockney is fascinated by human life and the narrative alongside this, Kellner’s interest lies entirely within architecture.

‘Kellner totally places on its head the basic impact of architecture, its sence of stability, permanence and order’

The idea of fragmenting an image indicates the influence of Cubism ‘He portrays great architecture in ways never intended, the familiar becomes scrambled and re-assembled – a technique which echoes Cubism and Hockney’

Kellner’s London eye uses 144 frames

‘to virtually explode this popular landmark into a dynamic mosaic of recurring patterns and shapes’ (Clark 2009) (Figure 8)

Kellner is cautious about how his work is described. ‘I think I am more of an artist than a photographer’ (Skinner 2005). There are various debates about photomontage and photo collage. In 2012 Kellner stated that ‘David Travis from the Art institute in Chicago was always sure my work was not a collage but a montage, whereas Weston Naef claimed collage as the only correct term for my work’. This is where his work differs from Hockney’s as he does not cut it up into pieces and then reattach it. Nor does Kellner believe his work can be defined as a ‘Joiner’.

‘It’s really complicated – name something without existing definitions’ (Kellner 2012)

When I asked Kellner if Hockney had influenced his work in any way he replied ‘When I started the work I only knew of one Polaroid grid that Hockney produced, it was in an exhibition catalogue from Kunsthalle Bielefeld about experimental photography’ (2012).

After his initial Eiffel Tower photographs, he saw a Hockney exhibition in Cologne in 1999

‘Kellner is closer to David Hockney and his idea of grasping something with multiple pictures, since a single photograph simply isn’t enough. (…) Thus, Thomas Kellner does not photograph architecture, but perceptions of architecture. He reconstructs our picture memory. He doesn’t document, he archives.’ (Misslebeck 2002)

Clearly Kellner differs from Hockney in the methodology he employs, namely calculating frame by frame and printing in the exact same sequence and size as he has taken them. They are not cut and pasted into a collage nor do they have a narrative style or sense of time as Hockney. However they are important pieces of unique art work in their own right, reflecting architectural icons. After the attack on the World Trade Centre, Kellner stated

‘I am still thinking about the parallels that my pictures have with that tragedy. These buildings that I photograph, like the Twin Towers, have become metaphors for a culture in fragments’ (Skinner 2005)

My favourite piece of Kellners has to be London, Tower Bridge (figure 9). Each of the towers has been re-shaped and stretched at the same time giving it new dimensions and height making it look almost mystical.

The Cubist art movement has been influential to so many people and has helped define much of the art work we see today including the photographic work of Kellner and Hockney. As quoted by Bate (2009) ‘The impact of art on photography cannot be underestimated’. Kellner and Hockney have of course continued to push the boundaries, both engage with the relationship between the representation of real spaces and places and their virtual equivalent of cubism. ‘Photography for its part, transformed the idea of art’ (Benjamin 1931)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books:

Bate, David, Photography - The key concepts, New York: Berg, 2009

Cunningham, Robert, Art explained, London: Dorling Kindersley Limited, 1995-2007

Cox, Neil, Cubism, London: Phaidon Press Limited, 2000

Joyce, Paul, Hockney on photography, London, Jonathan Cape Limited, 1988

Wye, Deborah, A Picasso portfolio: from the museum of Modern Art, New York, 2010

Rochon, L, Mission Control Exposed! Unique vision of mission control through the lense of photographer Thomas Kellner, Roundup, Pictures in time, 2010

Clark, David, Photography in a 100 words, London, Focal Press, 2009

Skinner, P, Thomas Kellner, Reconstructive iconographer, Rangefinder, 2005 pages 100-112, 118-119

Websites:

www.huntfor.com/arthistory/C20th/cubism.htm

www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/cube/hd_cube.htm

www.tate.org.uk/collections/glossary/definition.jsp

www.luminous-lint.com (Thomas Kellner – Dancing walls Article)

Video:

www.youtube.com/watch

Pictures:

Fig 1 - Picasso, The Guitar Player, 1910. Oil on canvas, 100cm x 73cm.

Fig 2 – Hockney, Sun On the Pool, 1982 composite Polaroid, 343/4 x 36 ¼ inch.

Fig 3 – Hockney, My House, Montcalm Avenue, 1982

Fig 4 – Hockney,

Fig 5 - Hockney, George, Blanche and Celia Albert, London (January 1983)

Fig 6 – Hockney, Jardin de Luxembourg, Paris (1985)

Fig 7 – Kellner, Paris Tour Eiffel, 1997

Fig 8 – Kellner, London Eye 2001

Fig 9 – Kellner, London Tower Bridge 2001